Kōlea claim territories in yards, hearts, and driveways

Kōlea on rear-view mirror. ©Tiana Burdick

Kōlea on rear-view mirror. ©Tiana Burdick

February 11, 2025

The kōlea season is going strong. Our birds are back, counters are counting, and plover lovers are sharing photos and stories that make my day. They’ll make your day too, as will the following results from your reports.

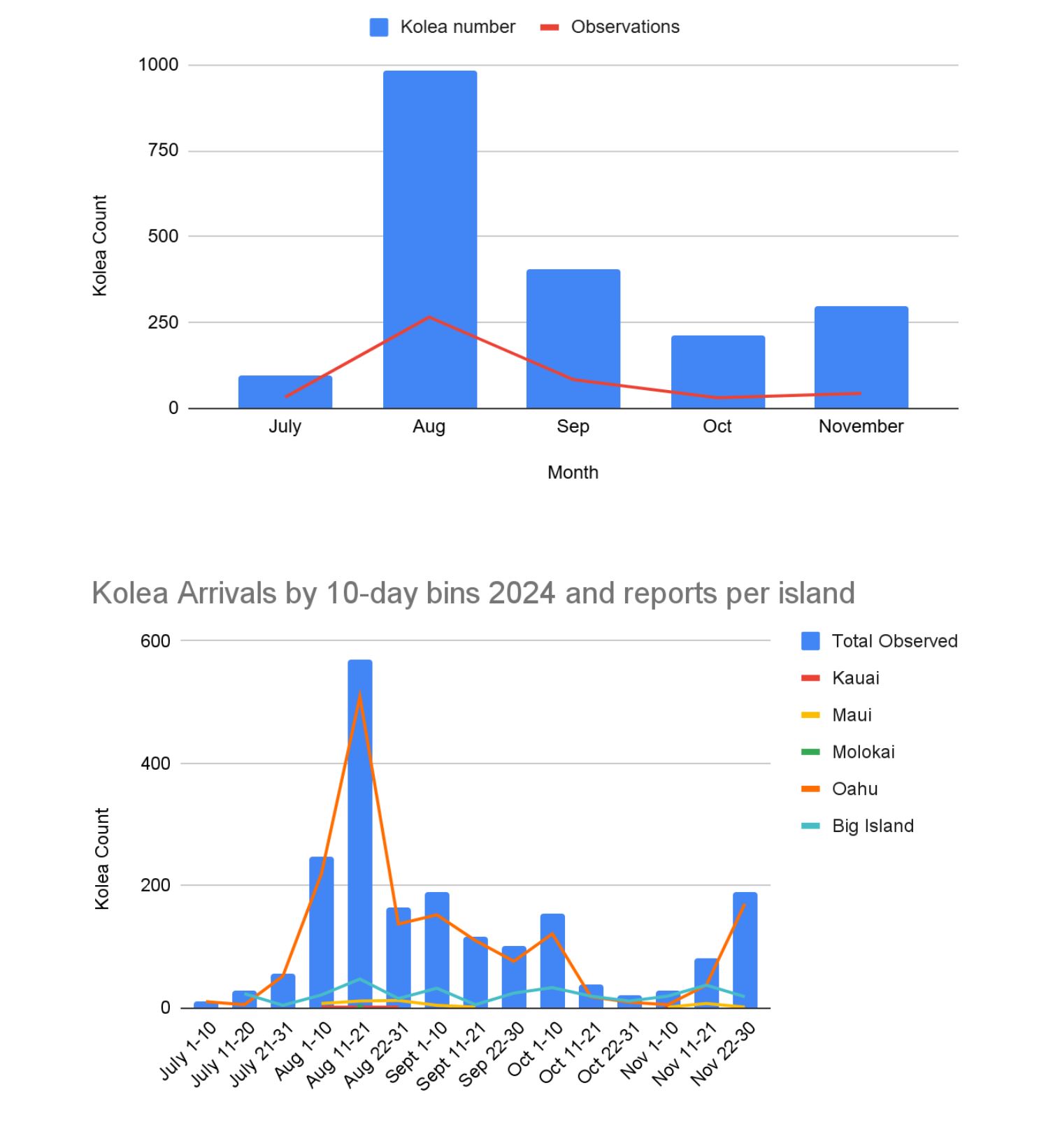

Thanks to Dr. Wendy Kuntz, biology professor at Kapiʻolani Community College and Hawaiʻi Audubon board member, we can see summaries of this season’s (2024) arrival data.

Most kōlea watchers reported seeing their first returnees in August.

From the Big Island: Our neighborhood kolea “Kula” was first spotted August 5, 2024 ~ 1:40pm. She arrived August 6th in 2022 & 2023. We’re happy, relieved, grateful she made it home! We’re enjoying Kula’s return…

A few birds arrived in July, either adults that failed to raise chicks or experienced adults that have this breeding thing down pat and fledged chicks early. Adult females usually return first.

From Kailua: Lady returned this morning, July 24, 2024. This completes her 10th full cycle with us. Interestingly, she returned in August the first 4 years but has since been returning in the latter third of July. Her July return dates have been remarkably consistent. Go, Lady. Hoping her offspring are equally successful.

A September arrival, Oahu North Shore. Because kōlea begin dropping their breeding feathers (molting) while still sitting on eggs in Alaska, it’s impossible to tell males from females when the birds arrive in Hawaiʻi. Some are mottled. This one is already wearing its winter outfit. ©Laura Zoller

A September arrival, Oahu North Shore. Because kōlea begin dropping their breeding feathers (molting) while still sitting on eggs in Alaska, it’s impossible to tell males from females when the birds arrive in Hawaiʻi. Some are mottled. This one is already wearing its winter outfit. ©Laura Zoller

Other kōlea watchers recorded birds arriving in their yards or parks as late as November. These are probably the summer’s chicks, which stay in Alaska as long as the weather is fair and bugs and berries are abundant. We should give these late comers a warm welcome. They gained enough weight to make the flight, survived Arctic predators, and successfully navigated to Hawaiʻi on their own. Bravo, kids.

This parent is guarding its newly-hatched chicks. Migratory shorebirds have so many obstacles to overcome it’s a miracle of nature that any survive at all. ©Wally Johnson

This parent is guarding its newly-hatched chicks. Migratory shorebirds have so many obstacles to overcome it’s a miracle of nature that any survive at all. ©Wally Johnson

This Citizen Science project is in its fourth year with some of us counting year after year, and others joining the fun for the first time. There’s no wrong way to count kōlea. All data, including zero, is useful. Rich Downs, another Hawaiʻi Audubon board member (and Hui Manu o Kū leader) is compiling KōleaCount data with eBird data to see where our birds spend winters, and in what concentrations. Results are pending at season’s end.

But besides numbers, locations, and dates, KōleaCount adds joy to counters lives. I know this from my own experience and from the notes and photos participants add with their observations.

Here are a few:

Some kōlea are extra friendly. From Mililani: This bird loves our son’s (new place, just moving) backyard! Isn’t very afraid …

This kōlea seems to be leading a parade of ʻakekeke, or ruddy turnstones. The species often forage together. Puʻuiki Cemetery in Waialua is one of the places I count. ©Susan Scott

This kōlea seems to be leading a parade of ʻakekeke, or ruddy turnstones. The species often forage together. Puʻuiki Cemetery in Waialua is one of the places I count. ©Susan Scott  A newly hatched kōlea chick in Alaska. Legs are adult-sized at hatching. ©Wally Johnson

A newly hatched kōlea chick in Alaska. Legs are adult-sized at hatching. ©Wally Johnson  Shorebird parents don’t feed their chicks but follow the youngsters as they forage. Parents sit on their chicks to warm them when weather turns stormy. ©Wally Johnson

Shorebird parents don’t feed their chicks but follow the youngsters as they forage. Parents sit on their chicks to warm them when weather turns stormy. ©Wally Johnson  When this young plover (left) trespassed on another’s patch, the established owner put up a fight. The squabble occurred in Punchbowl Cemetery. The newcomer moved on. (First year birds have no breeding colors.) ©Susan Scott

When this young plover (left) trespassed on another’s patch, the established owner put up a fight. The squabble occurred in Punchbowl Cemetery. The newcomer moved on. (First year birds have no breeding colors.) ©Susan Scott

Four kōlea: From left, the new kōlea-in-tuxedo flag, mascot Kōlea Nui, volunteer Andres Jojoa Ortega in his EVERY KŌLEA COUNTS T-shirt, and lower right, a curious resident kōlea checking out its namesakes. © Christiaan Phleger

Four kōlea: From left, the new kōlea-in-tuxedo flag, mascot Kōlea Nui, volunteer Andres Jojoa Ortega in his EVERY KŌLEA COUNTS T-shirt, and lower right, a curious resident kōlea checking out its namesakes. © Christiaan Phleger  Hawaiʻi Audubon’s Team Kōlea: Foreground from left, Operations Manager Laura Doucette, me, mascot Kōlea Nui, and Education Manager, Elena Arinaga. Left background are Taylor Kim and Charlotte Bender, two of four Kapiolani Community College students who helped with the festival.

Hawaiʻi Audubon’s Team Kōlea: Foreground from left, Operations Manager Laura Doucette, me, mascot Kōlea Nui, and Education Manager, Elena Arinaga. Left background are Taylor Kim and Charlotte Bender, two of four Kapiolani Community College students who helped with the festival.

MJ Mazurek gives Kōlea Nui (AKA Josh Fisher) a cold drink of water. Even with an ice-pack vest and a head fan, hugging and dancing with children is hot work. Volunteers took turns wearing the costume. ©Susan Scott

MJ Mazurek gives Kōlea Nui (AKA Josh Fisher) a cold drink of water. Even with an ice-pack vest and a head fan, hugging and dancing with children is hot work. Volunteers took turns wearing the costume. ©Susan Scott  Representatives of the new drink, Kōlea Sparkling Hop Water, (zero alcohol, zero calories) shared the Kōlea Festival with us. Everyone enjoyed the free samples, as well as the company’s logo. ©Susan Scott

Representatives of the new drink, Kōlea Sparkling Hop Water, (zero alcohol, zero calories) shared the Kōlea Festival with us. Everyone enjoyed the free samples, as well as the company’s logo. ©Susan Scott

Puuiki Cemetery, Waialua September 2, 2024. ©Susan Scott

Puuiki Cemetery, Waialua September 2, 2024. ©Susan Scott  A Lowe’s parking lot kōlea. Elton Miyagawa photo.

A Lowe’s parking lot kōlea. Elton Miyagawa photo.  Hawaii Audubon Society members show off their kōlea fandom at Hoʻomaluhia Botanical Garden on September 6. Memberships and Ts, available at Hawaii Audubon.org, help support research and education.

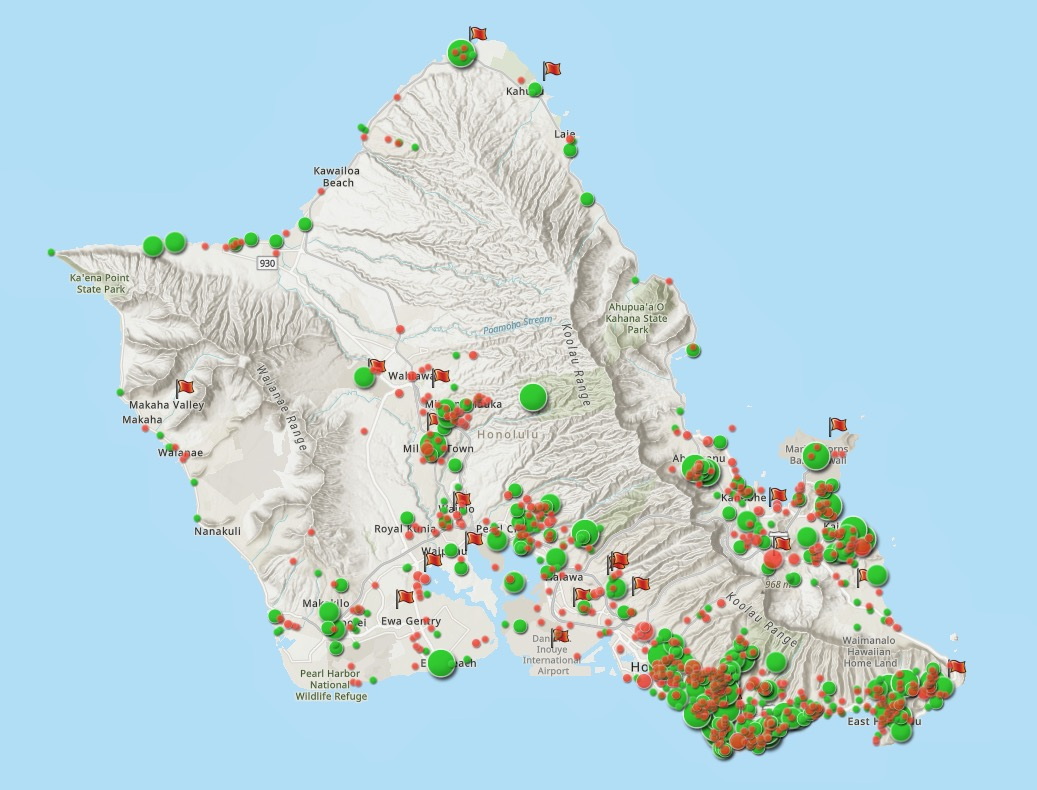

Hawaii Audubon Society members show off their kōlea fandom at Hoʻomaluhia Botanical Garden on September 6. Memberships and Ts, available at Hawaii Audubon.org, help support research and education.  Flags show golf courses, ideal habitat for our kōlea but currently far under-counted. Green dots are kōlea locations reported in 2023-2024 season. Orange dots are plovers reported in previous years but not 2023-2024. Dot sizes reflect number of years reported. Rich Downs image.

Flags show golf courses, ideal habitat for our kōlea but currently far under-counted. Green dots are kōlea locations reported in 2023-2024 season. Orange dots are plovers reported in previous years but not 2023-2024. Dot sizes reflect number of years reported. Rich Downs image.  Kōlea Count and eBird data layered over a Hawaii Land Cover map. Rich Downs image.

Kōlea Count and eBird data layered over a Hawaii Land Cover map. Rich Downs image.

This sign demanded a photo stop during a Hilo visit last year. The kōlea (upper left image on sign) is apparently the Chiefess Kapiʻolani Elementary School’s mascot. ©Wendy Kuntz

This sign demanded a photo stop during a Hilo visit last year. The kōlea (upper left image on sign) is apparently the Chiefess Kapiʻolani Elementary School’s mascot. ©Wendy Kuntz

Bougie has returned to this space off Crozier Drive in Waialua for at least five years. (Zebra dove in foreground.) Our phone cameras may not take the best distance photos, but they’re in our pockets to capture the moment.

Bougie has returned to this space off Crozier Drive in Waialua for at least five years. (Zebra dove in foreground.) Our phone cameras may not take the best distance photos, but they’re in our pockets to capture the moment.  From Wally Johnson’s tracking studies. © O.W. Johnson

From Wally Johnson’s tracking studies. © O.W. Johnson  July 25, 2024, Oahu, undisclosed location) © Ann Egleston

July 25, 2024, Oahu, undisclosed location) © Ann Egleston  August 9, 2024, Kamehameha soccer field, Hilo ©Jo-Ann Garrigan

August 9, 2024, Kamehameha soccer field, Hilo ©Jo-Ann Garrigan  July 25, Niu Valley, © Patricia Johnson

July 25, Niu Valley, © Patricia Johnson  August 2, Hilo Public Library, © Jo-Ann Garrigan

August 2, Hilo Public Library, © Jo-Ann Garrigan  August 6, Kuahelani Park, Mililani © Tempe Kapela

August 6, Kuahelani Park, Mililani © Tempe Kapela  July 30, Waiau district Park, © Evelyn Nakanishi

July 30, Waiau district Park, © Evelyn Nakanishi

A kōlea on the Nome tundra. ©Susan Scott

A kōlea on the Nome tundra. ©Susan Scott  ©Laura Doucette

©Laura Doucette  Wally’s long-time field workers, Paul and Nancy Brusseau, scouting for kōlea. ©Susan Scott

Wally’s long-time field workers, Paul and Nancy Brusseau, scouting for kōlea. ©Susan Scott  Members of our group looking for birds. ©Susan Scott

Members of our group looking for birds. ©Susan Scott  ©Susan Scott

©Susan Scott  ©Susan Scott

©Susan Scott  ©Laura Doucette

©Laura Doucette  Wally posed this question: If we tall humans have a hard time finding a nest, how do little birds do it? This photo, taken by me on my belly, as Wally suggested, is a kōlea-eye view of the tundra. ©Susan Scott

Wally posed this question: If we tall humans have a hard time finding a nest, how do little birds do it? This photo, taken by me on my belly, as Wally suggested, is a kōlea-eye view of the tundra. ©Susan Scott

Besides learning new things, kōlea help us to make new friends. Plover fan Roger Kobayashi (right) hosts me several times a year at Ford Island (a contractor working there took this photo of us) and Tripler Army Medical Center to watch kōlea gather. On Saturday, only 6 birds remained, a gradual decrease from a high of 110.

Besides learning new things, kōlea help us to make new friends. Plover fan Roger Kobayashi (right) hosts me several times a year at Ford Island (a contractor working there took this photo of us) and Tripler Army Medical Center to watch kōlea gather. On Saturday, only 6 birds remained, a gradual decrease from a high of 110.  This kōlea learned to eat mealworms from the home owner’s hand. The bird returned to the man’s Kailua yard for 15 years.

This kōlea learned to eat mealworms from the home owner’s hand. The bird returned to the man’s Kailua yard for 15 years.

If you feed your bird, please offer high protein food, such as worms or scrambled egg. This is my Jake, at least eight years old, eating his egg. His last day on my lanai was April 20th.

If you feed your bird, please offer high protein food, such as worms or scrambled egg. This is my Jake, at least eight years old, eating his egg. His last day on my lanai was April 20th.

Roger Kobayashi unfolds chairs for our kōlea watch. ©Susan Scott

Roger Kobayashi unfolds chairs for our kōlea watch. ©Susan Scott

From our distance, the male/female mix seemed about equal. ©Susan Scott

From our distance, the male/female mix seemed about equal. ©Susan Scott  The black dots in this Tripler Army Medical Center (pink building) field are kōlea. ©Susan Scott

The black dots in this Tripler Army Medical Center (pink building) field are kōlea. ©Susan Scott  After Roger contacted me with the gathering news, I drove to Kualoa Park to see if kōlea are gathering there. They were not. I’ll keep checking. ©Susan Scott

After Roger contacted me with the gathering news, I drove to Kualoa Park to see if kōlea are gathering there. They were not. I’ll keep checking. ©Susan Scott