Join us for the 2022-2023 Kōlea Count

November 22, 2022

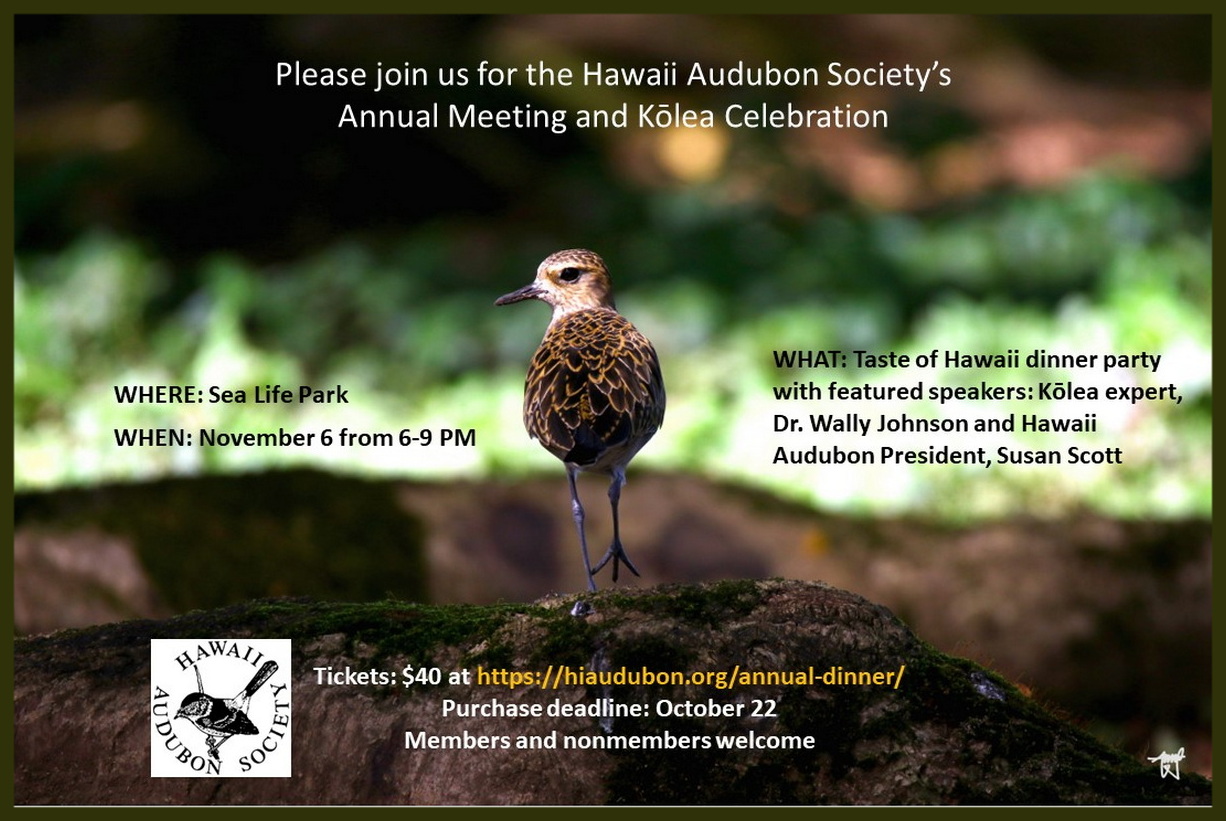

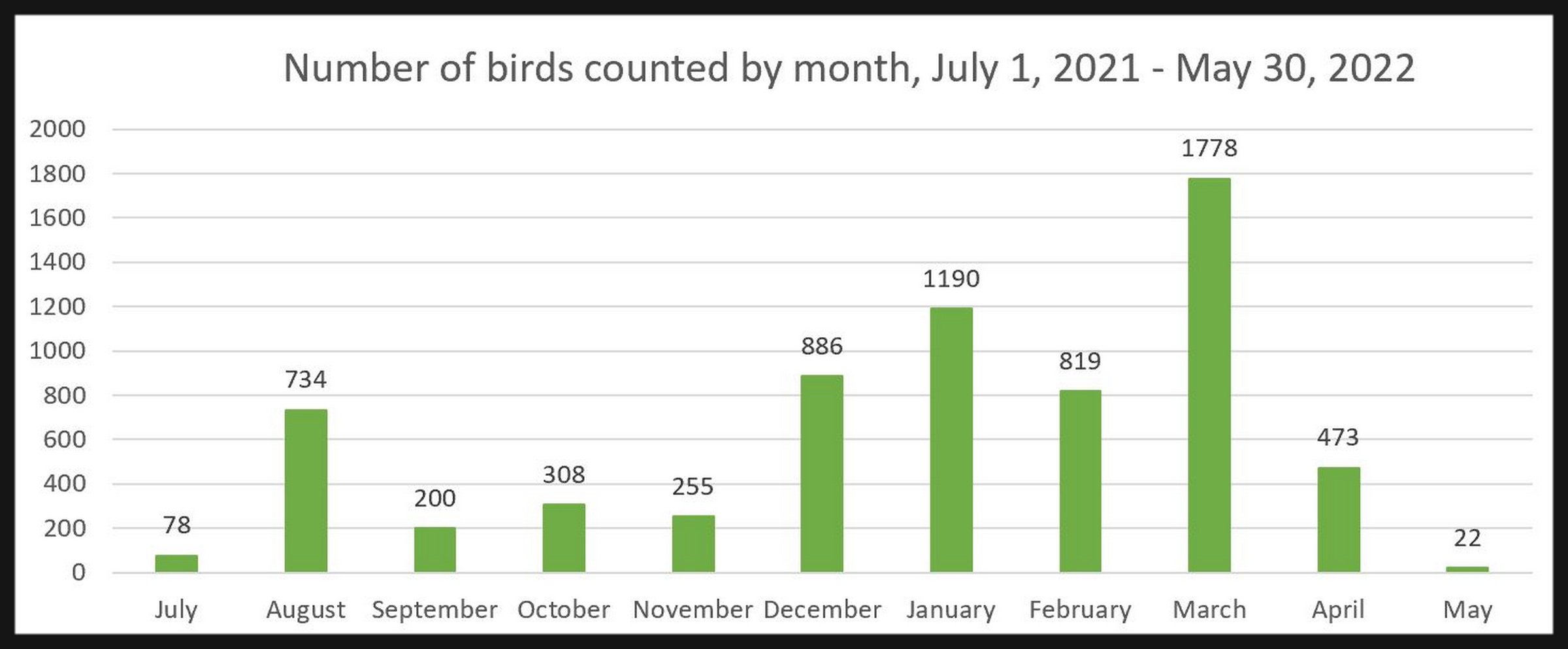

Welcome to the third annual Kōlea Count, the Hawaii Audubon Society’s citizen science project started in 2020. Because so many facts about these remarkable shorebirds are still unknown, and so many Hawaiʻi residents and visitors watch and enjoy our plovers, here’s an opportunity for us to record our observations.

Adults arrive from their Alaska breeding ground in July, August, and September. The summer’s offspring stay in Alaska until the snow falls, sometimes as late as October and November. With food sources gone, the youngsters head south alone. It’s a perilous journey, but juveniles that live through their first winter have the potential to live 20 or more years.

Birdy Big Foot: Kōlea chicks hatch with adult-sized feet and legs, and can fly in about a month. This chick is on the tundra near Nome, Alaska. © Oscar W. Johnson.

Birdy Big Foot: Kōlea chicks hatch with adult-sized feet and legs, and can fly in about a month. This chick is on the tundra near Nome, Alaska. © Oscar W. Johnson.

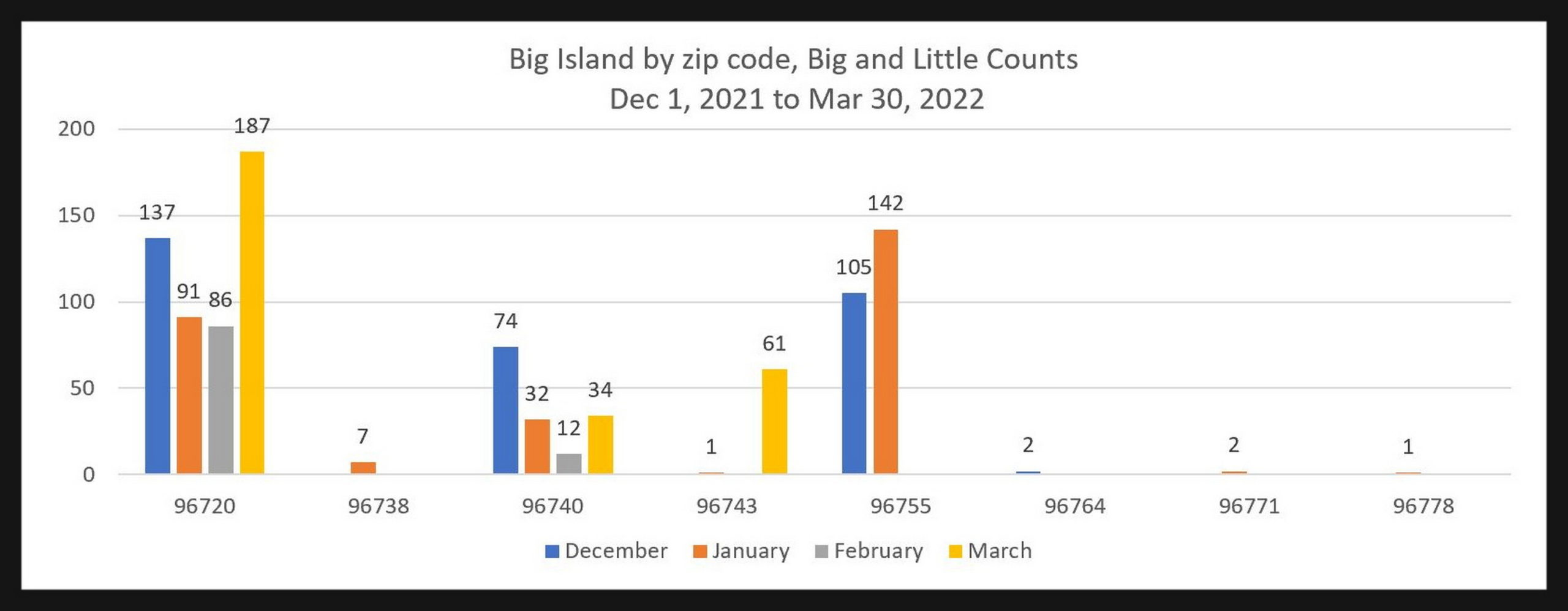

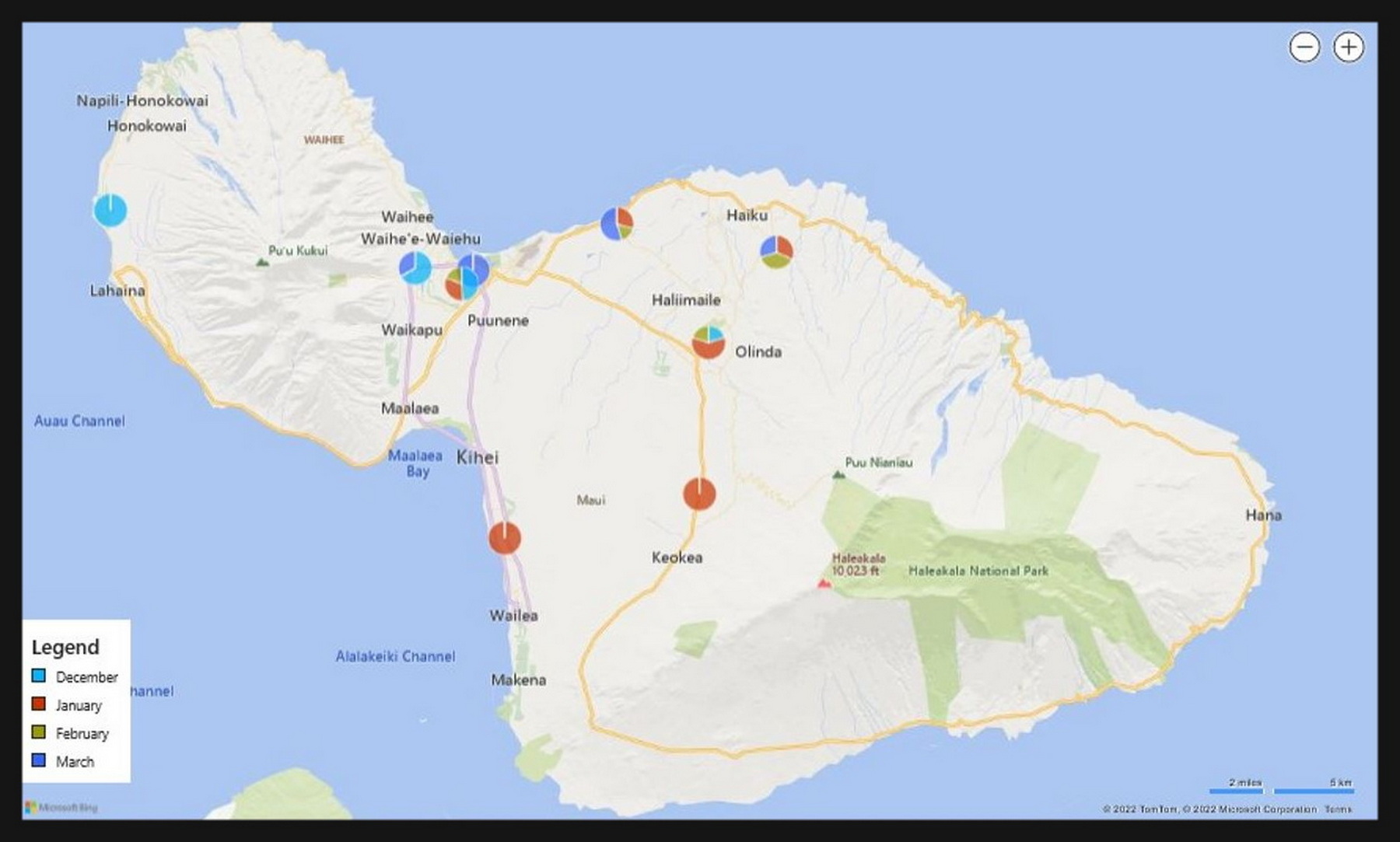

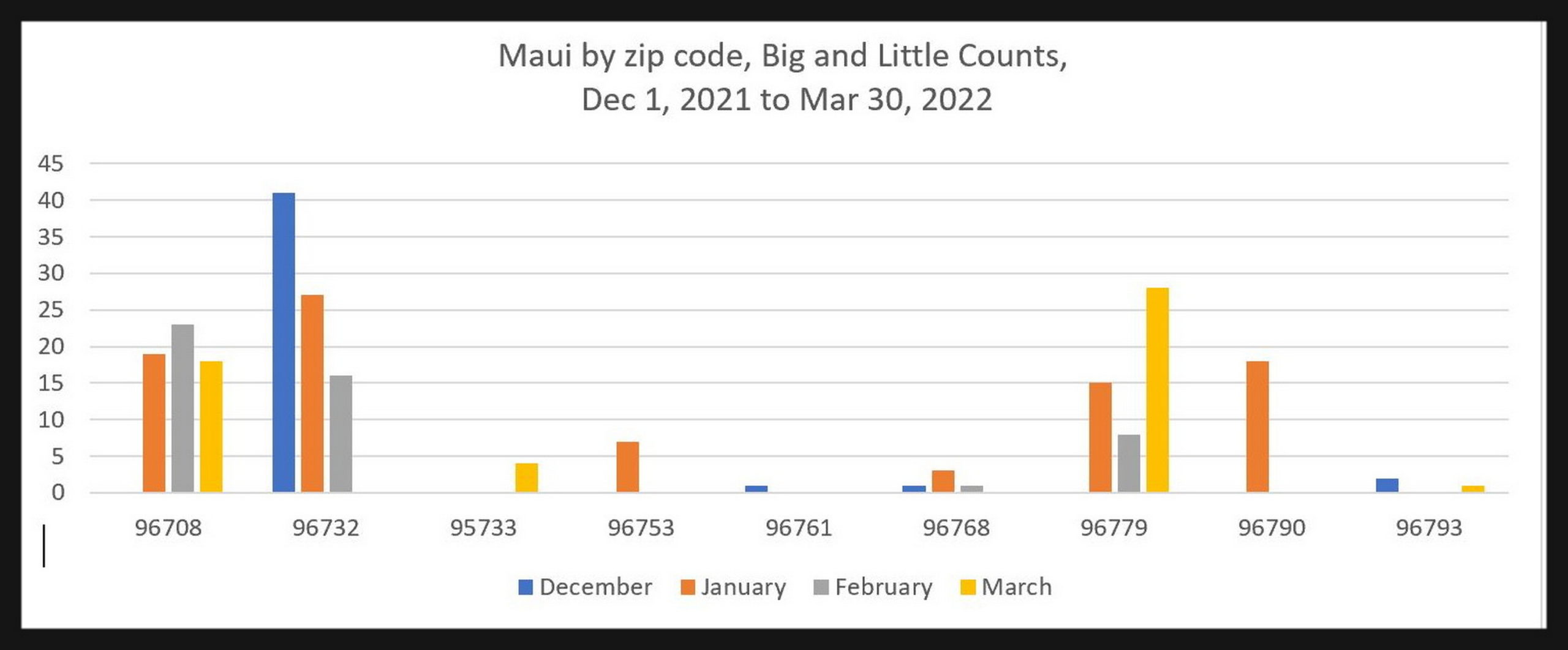

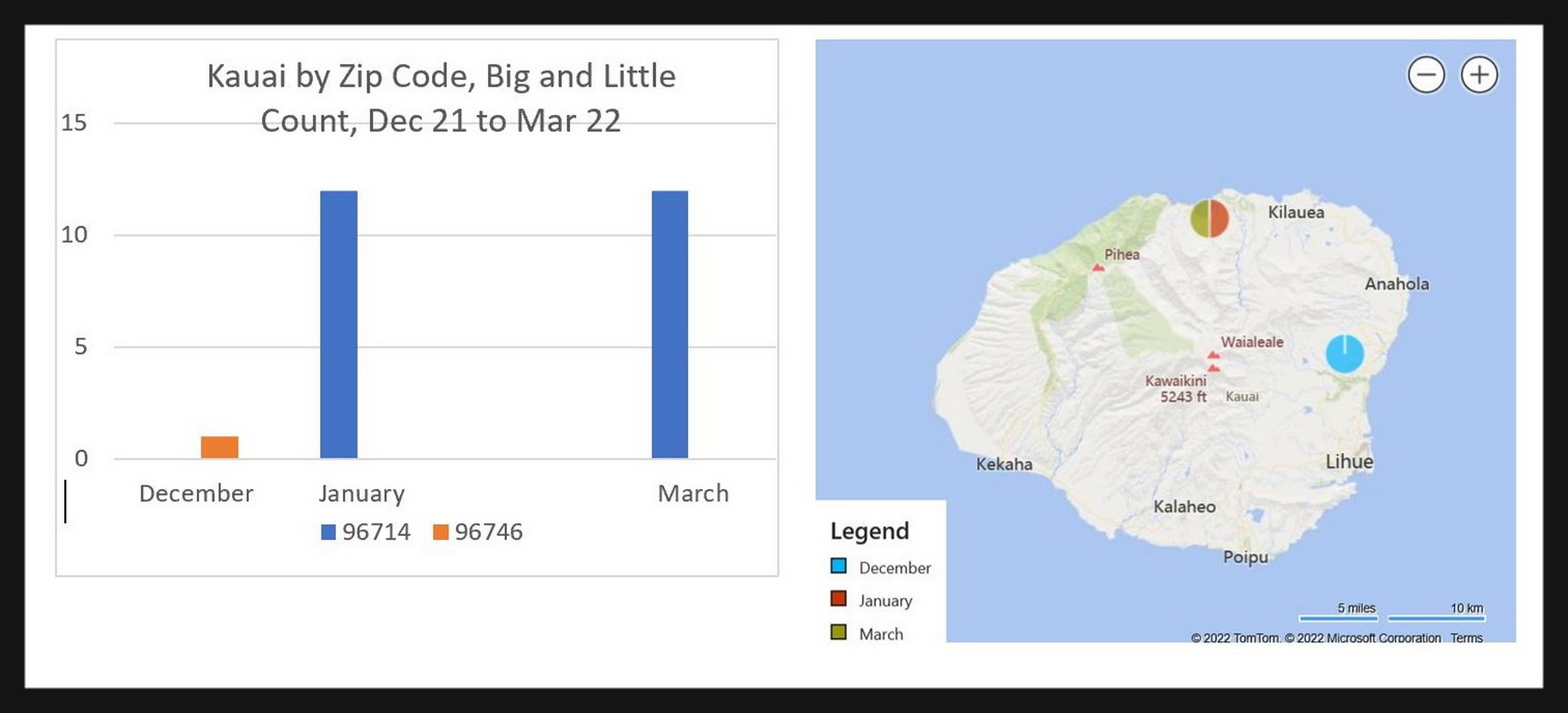

The birds that survived Arctic predators, stormy weather, and competition for space are now here in Hawaiʻi. So let’s don our green Kōlea T-shirts, and go counting. We ask for a minimum (no maximum) of three counts in each area, from December 1st through March 31st.

T-shirts available at hiaudubon.org.

T-shirts available at hiaudubon.org.

Counting goals are to:

- Get some numbers. Collecting data to compare from year-to-year will help us learn more about whether Hawai’i’s plover population is increasing, decreasing, or staying the same.

- Spread the joy. The Kōlea that winter in Hawaii are the only shorebirds in the world that have adapted so well to human presence, and to our alteration of the birds’ natural habitats. Our plovers stroll down sidewalks, sleep on rooftops, forage in lawns, and get fat on the hundreds of species we’ve introduced to the Islands. (Plovers eat anything that crawls.)

Kōlea pick bugs from Astroturf and bathe in hotel swimming pools. Kauai. ©Susan Scott

Kōlea pick bugs from Astroturf and bathe in hotel swimming pools. Kauai. ©Susan Scott

Please see the GUIDELINES tab to sign up for a LITTLE COUNT or a BIG COUNT. Ask questions or share comments with me on the CONTACT tab.

On behalf of our lovely, perky Kōlea, thank you for helping us learn more about them and in that, learn how to help them thrive.

Punchbowl Cemetery, Oahu’s Kōlea lab. © Sigrid Southworth (our Punchbowl Kōlea counter.)

Punchbowl Cemetery, Oahu’s Kōlea lab. © Sigrid Southworth (our Punchbowl Kōlea counter.)

Aloha, Susan Scott, Plover lover and Hawaii Audubon Society president

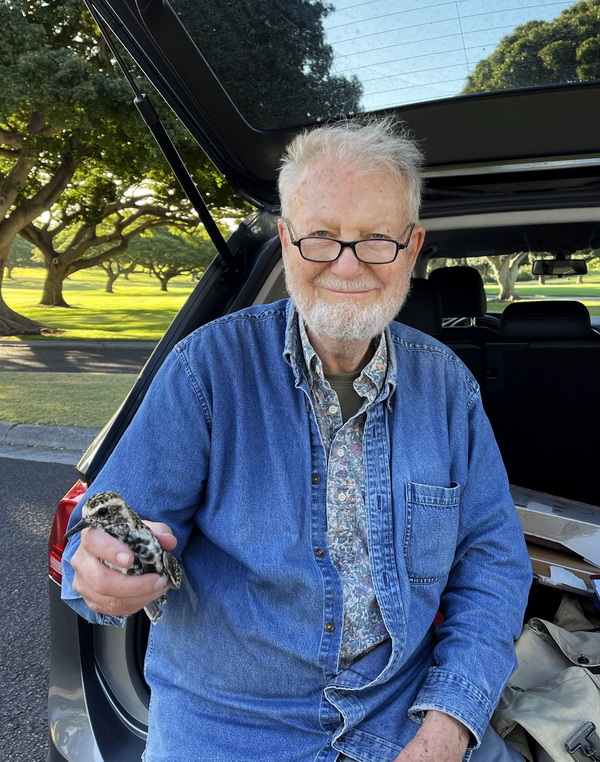

Wally and me (Susan) giving a Kōlea ID leg bands at Punchbowl Cemetery, March, 2022.

Wally and me (Susan) giving a Kōlea ID leg bands at Punchbowl Cemetery, March, 2022.

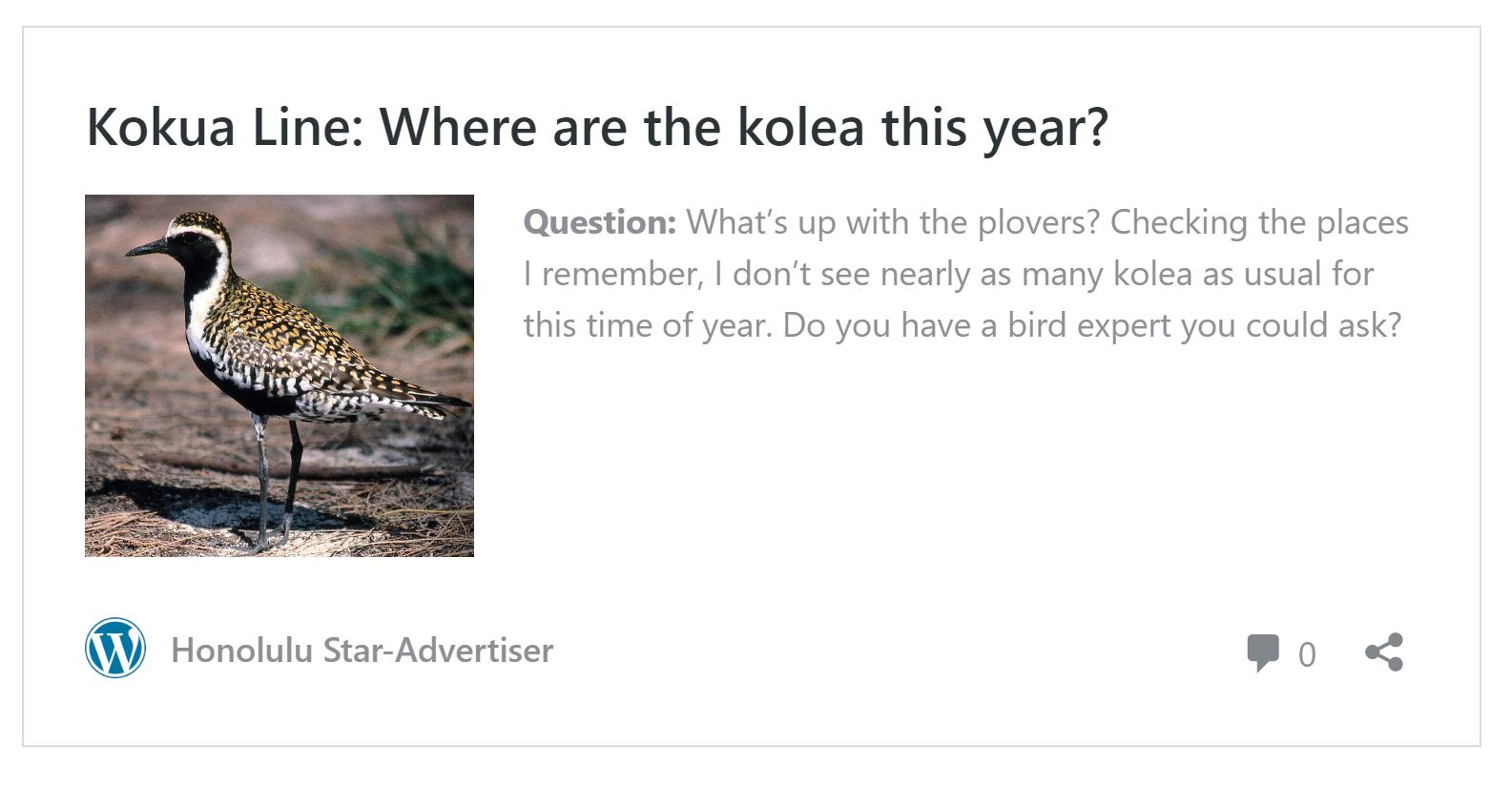

The above clip is from the September 3rd, 2022 Kokua Line. My answers are available only to Star-Advertiser subscribers, but the facts I gave Christine are below, as well as on this website. On September 9th, I also chatted about kōlea with Catherine Cruz, host of Hawaii Public Radio’s “The Conversation.”

The above clip is from the September 3rd, 2022 Kokua Line. My answers are available only to Star-Advertiser subscribers, but the facts I gave Christine are below, as well as on this website. On September 9th, I also chatted about kōlea with Catherine Cruz, host of Hawaii Public Radio’s “The Conversation.”  Between 70 and 80 kōlea spend winters in Punchbowl Cemetery. This is the first to arrive back in its Punchbowl patch, spotted by the Hawaii Audubon Society’s office and communications manager, Laura Zoller on August 7, 2022. ©Laura Zoller

Between 70 and 80 kōlea spend winters in Punchbowl Cemetery. This is the first to arrive back in its Punchbowl patch, spotted by the Hawaii Audubon Society’s office and communications manager, Laura Zoller on August 7, 2022. ©Laura Zoller  This bird posed perfectly for a picture of its leg bands. The plover returned to Punchbowl on August 22nd, and appeared to be good health after flying 6,000 round-trip miles carrying a tiny satellite tag. (antenna below tail.) © Susanne Spiessberger

This bird posed perfectly for a picture of its leg bands. The plover returned to Punchbowl on August 22nd, and appeared to be good health after flying 6,000 round-trip miles carrying a tiny satellite tag. (antenna below tail.) © Susanne Spiessberger

Our Jake on April 1st. ©Susan Scott

Our Jake on April 1st. ©Susan Scott  During my visit to the Ford Island field, Roger and I counted about 50 birds in the field. Because they tended to line up lengthwise, less than half are visible in this picture. ©Susan Scott

During my visit to the Ford Island field, Roger and I counted about 50 birds in the field. Because they tended to line up lengthwise, less than half are visible in this picture. ©Susan Scott  Punchbowl study female, April 20, 2022.©Susan Scott

Punchbowl study female, April 20, 2022.©Susan Scott  Another Punchbowl study male, April 26, 2022 ©Susan Scott

Another Punchbowl study male, April 26, 2022 ©Susan Scott

The plover carries its lightweight satellite tag on its back with soft, stretchable straps around the upper part of each leg. This allows the birds to walk and fly unhindered. ©Susan Scott

The plover carries its lightweight satellite tag on its back with soft, stretchable straps around the upper part of each leg. This allows the birds to walk and fly unhindered. ©Susan Scott  Volunteer, Marcy Katz, enjoys holding a satellite-tagged bird (antenna below its tail) before releasing it. Because Pacific Golden-Plovers defend their foraging areas, Wally makes sure each bird is returned to its home patch to avoid squabbles. ©Susan Scott

Volunteer, Marcy Katz, enjoys holding a satellite-tagged bird (antenna below its tail) before releasing it. Because Pacific Golden-Plovers defend their foraging areas, Wally makes sure each bird is returned to its home patch to avoid squabbles. ©Susan Scott

This Maui Kolea enjoyed bathing in a driveway rain puddle. © Photo courtesy Calvin M. Kaya, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Biology, Montana State University

This Maui Kolea enjoyed bathing in a driveway rain puddle. © Photo courtesy Calvin M. Kaya, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Biology, Montana State University  Craig is showing off the Pacific Golden-Plover patch on my Alaska Audubon hat, a special gift. Friend and neighbor Lani Twomey braved the storm to count Kolea with us. (Selfie)

Craig is showing off the Pacific Golden-Plover patch on my Alaska Audubon hat, a special gift. Friend and neighbor Lani Twomey braved the storm to count Kolea with us. (Selfie)  The Christmas Day Kolea team from right, David Johnson. Beth Flint, Craig Thomas and me, Susan Scott. Photo by Michelle Hester

The Christmas Day Kolea team from right, David Johnson. Beth Flint, Craig Thomas and me, Susan Scott. Photo by Michelle Hester  During the storm, stilts, ducks and people enjoyed the temporary lake on this fairway. © Susan Scott

During the storm, stilts, ducks and people enjoyed the temporary lake on this fairway. © Susan Scott  For reasons known only to the Kolea, the birds sometimes line up on the runway at Midway Atoll. © Courtesy Jonathan Plissner, USFWS

For reasons known only to the Kolea, the birds sometimes line up on the runway at Midway Atoll. © Courtesy Jonathan Plissner, USFWS

This Jaeger (pronounced YAY-gur, German for hunt) is a fast-flying gull relative that, like Kolea, nests on the ground in the Arctic tundra. Jaegers are predators that eat other birds and their eggs. This post on the tundra outside Nome was a good perch for scouting prey. ©Susan Scott

This Jaeger (pronounced YAY-gur, German for hunt) is a fast-flying gull relative that, like Kolea, nests on the ground in the Arctic tundra. Jaegers are predators that eat other birds and their eggs. This post on the tundra outside Nome was a good perch for scouting prey. ©Susan Scott  Although usually spread out on the sides of the Dillingham Airfield, these Kolea gathered on on the roadside during sky-diving activities. ©Susan Scott

Although usually spread out on the sides of the Dillingham Airfield, these Kolea gathered on on the roadside during sky-diving activities. ©Susan Scott

Ms. Ed. ©Susan Scott

Ms. Ed. ©Susan Scott  Bilbo taking a shower. ©Susan Scott

Bilbo taking a shower. ©Susan Scott  Roger Kobayashi sent a Google map of Ford Island, marking X, Y, and Z as to his first Kolea sightings, August 1, 2021.

Roger Kobayashi sent a Google map of Ford Island, marking X, Y, and Z as to his first Kolea sightings, August 1, 2021.  Wally, the bird, enjoying a scrambled egg offering. Please feed your bird only healthy food, such as scrambled egg or mealworms. ©Roger Kobayashi

Wally, the bird, enjoying a scrambled egg offering. Please feed your bird only healthy food, such as scrambled egg or mealworms. ©Roger Kobayashi

Mr. X in his territory in March, 2021 with all three leg bands. ©Sigrid Southworth.

Mr. X in his territory in March, 2021 with all three leg bands. ©Sigrid Southworth.  Researchers can place adult-sized leg bands, shown here, on newly hatched Kolea chicks. The youngsters begin foraging for insects and berries soon after hatching. Parents warm and protect their offspring, but do not feed them. Near Nome, Alaska © Oscar Johnson. …

Researchers can place adult-sized leg bands, shown here, on newly hatched Kolea chicks. The youngsters begin foraging for insects and berries soon after hatching. Parents warm and protect their offspring, but do not feed them. Near Nome, Alaska © Oscar Johnson. …