Kolea update Tuesday, August 6, Hula Grill Waikiki

A kōlea on the Nome tundra. ©Susan Scott

A kōlea on the Nome tundra. ©Susan Scott

July 8, 2024

Hawaiʻi walks are always good, but not quite as good from May through July, when our kōlea are in Alaska. We plover lovers feel the birds’ absence, and often wonder how they’re doing with their summer job of chick-rearing.

Some of us went to see for ourselves From June 24-28, the Hawaiʻi Audubon Society sponsored its second Kōlea Quest trip to Nome. And once again, we had the privilege of accompanying world plover authority, Dr. O. Wally Johnson, and his two research associates from Anchorage. (Photo below. Wally, brown coat, in center.)

©Laura Doucette

©Laura Doucette

For Hawaiʻi residents accustomed to friendly kōlea that prance around our backyards and eat scrambled eggs on our lanais, Alaska kōlea hold a surprise: While breeding, the birds view humans as predators, up there with foxes, ravens, jaegers, and all the other Arctic animals hunting for food. With predators on the prowl for nutritious eggs and chicks, the lives of plovers, and all ground-nesting birds on the tundra, are filled with life-and-death drama. Camouflage, hunkering down, and holding motionlessness are keys to survival, making finding even one kōlea nest a challenge.

Wally’s long-time field workers, Paul and Nancy Brusseau, scouting for kōlea. ©Susan Scott

Wally’s long-time field workers, Paul and Nancy Brusseau, scouting for kōlea. ©Susan Scott

Members of our group looking for birds. ©Susan Scott

Members of our group looking for birds. ©Susan Scott

But we were there with the experts. Over several days, the experienced researchers found three plover nests with eggs. Photos below. (O.W. Johnson USGS research permit #20957.)

©Susan Scott

©Susan Scott

©Susan Scott

©Susan Scott

And on our last day, one of those nests produced the thrill of a lifetime for kōlea fans: two new hatchings and one pipping (and peeping) egg. The first tiny hatchling was already running around the nest.

©Laura Doucette

©Laura Doucette

Like chickens, kōlea parents don’t feed their offspring. As soon as hatchlings’ downy feathers are dry, the kids are out and about, foraging for insects and berries. Parents follow the best they can, warming and protecting the chicks as needed.

Wally posed this question: If we tall humans have a hard time finding a nest, how do little birds do it? This photo, taken by me on my belly, as Wally suggested, is a kōlea-eye view of the tundra. ©Susan Scott

Wally posed this question: If we tall humans have a hard time finding a nest, how do little birds do it? This photo, taken by me on my belly, as Wally suggested, is a kōlea-eye view of the tundra. ©Susan Scott

In this bug-filled, light-all-night environment, chicks grow up fast. In one month, baby plovers can fly. Parents fly south in August, leaving their offspring on the tundra to fatten up as long as food is available. That can last into October, or even November, depending on weather. When snow falls, the summer’s chicks migrate to warm wintering grounds, instinct being their only guide.

This was the Hawaiʻi Audubon Society’s second trip to Nome with Wally, his study partners, …

April 29, 2024

Thanks to Hawaiʻi’s residents and visitors who care about the remarkable migratory shorebirds we call kōlea, the Kōlea Count project had another season loaded with information. And that’s the point. As we kōlea watchers report what, when, and where we see our plovers in the Islands, we learn more about the birds as well as the people who love them.

Besides learning new things, kōlea help us to make new friends. Plover fan Roger Kobayashi (right) hosts me several times a year at Ford Island (a contractor working there took this photo of us) and Tripler Army Medical Center to watch kōlea gather. On Saturday, only 6 birds remained, a gradual decrease from a high of 110.

Besides learning new things, kōlea help us to make new friends. Plover fan Roger Kobayashi (right) hosts me several times a year at Ford Island (a contractor working there took this photo of us) and Tripler Army Medical Center to watch kōlea gather. On Saturday, only 6 birds remained, a gradual decrease from a high of 110.

Some of what we learn in Kōlea Count is natural science, such as the dates the birds come and go in Hawaiʻi. Other details are social, such as the relationships Hawaiʻi people have with the birds. Last year during Hawaiʻi Audubon Society’s Alaska visit, Nome residents were astonished to hear that our plovers are on friendly terms with us. Another reason our kōlea are special.

This kōlea learned to eat mealworms from the home owner’s hand. The bird returned to the man’s Kailua yard for 15 years.

This kōlea learned to eat mealworms from the home owner’s hand. The bird returned to the man’s Kailua yard for 15 years.

Bottom line: It’s all good. You can’t do it wrong.

If you feed your bird, please offer high protein food, such as worms or scrambled egg. This is my Jake, at least eight years old, eating his egg. His last day on my lanai was April 20th.

If you feed your bird, please offer high protein food, such as worms or scrambled egg. This is my Jake, at least eight years old, eating his egg. His last day on my lanai was April 20th.

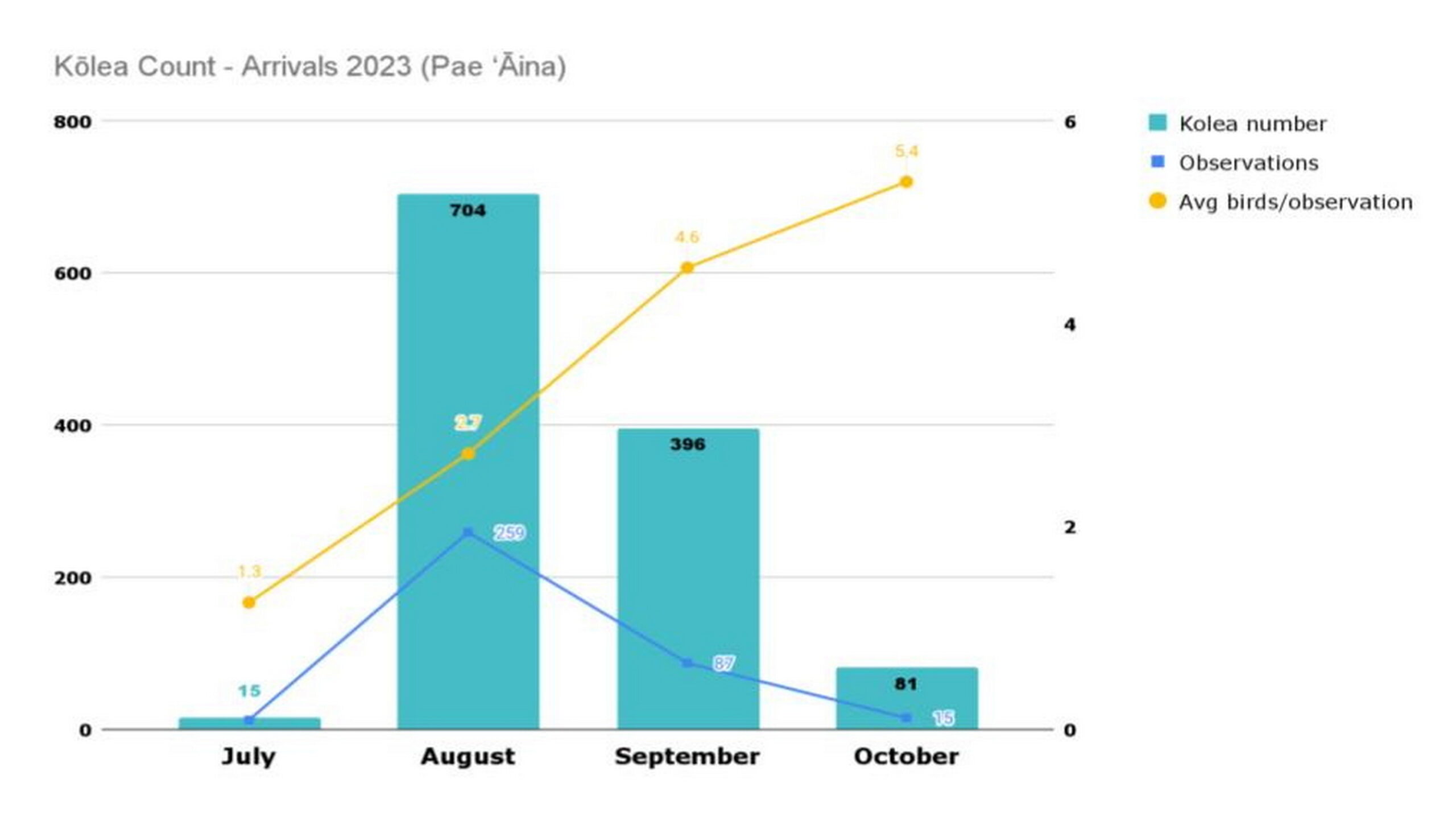

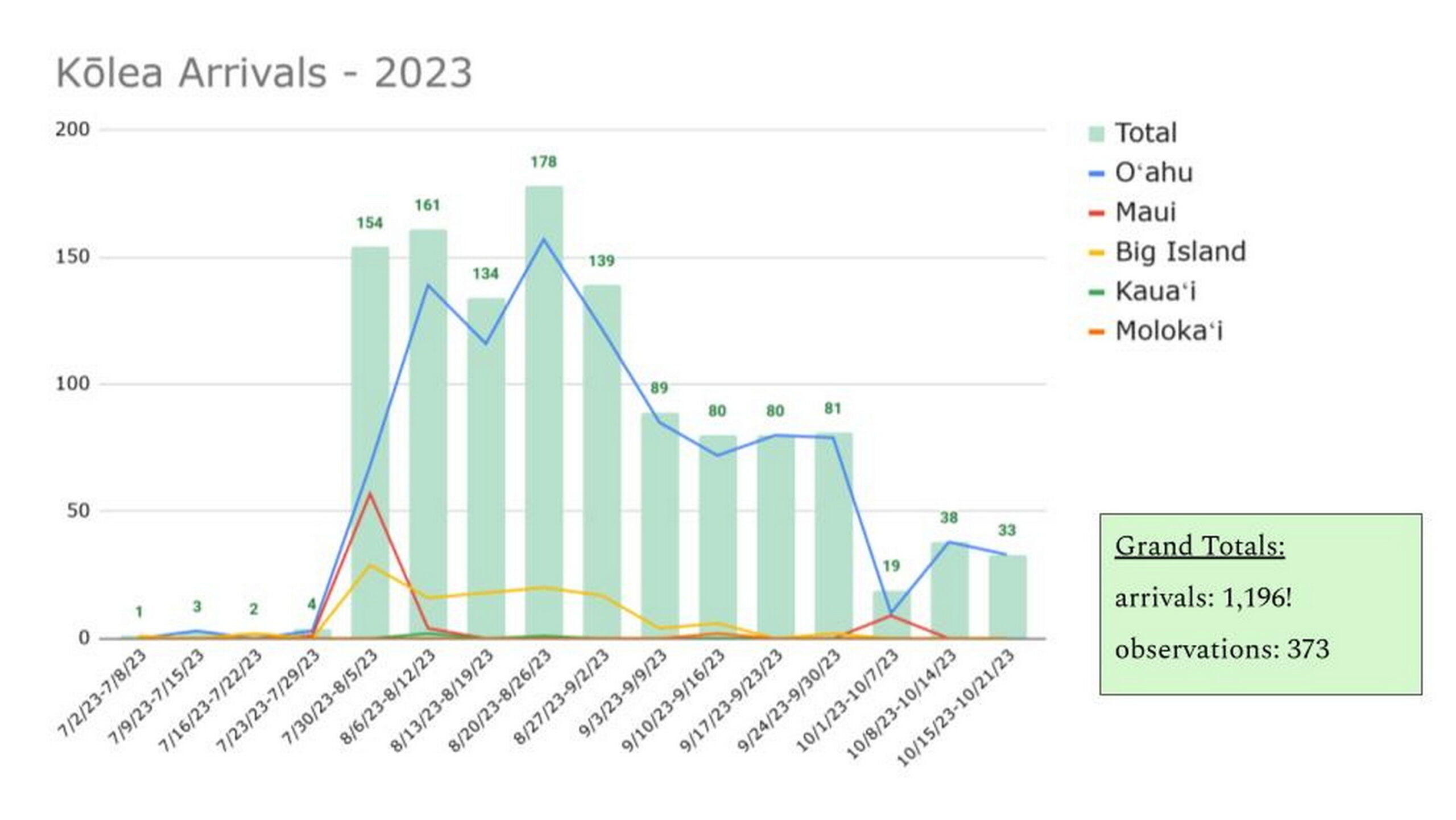

As for the state’s estimated plover population, several volunteers are currently analyzing our counts, along with eBird reports. I’ll share the resulting maps and charts when they’re available. In the meantime, below are some arrival data we know from your reports.

Starting in late July, 486 plover lovers entered the date they saw their first kolea return from Alaska. Report numbers ranged from one bird to 56 individuals at Tripler Army Medical Center. UHM graduate student, Claire Atkins, created the below graphs using that arrival data.

Most of our plovers have departed but a few are still here. I’ll share reported departure dates the end of May. Please report birds you see in June in the SUMMERING-OVER tab. July starts a new season when the earliest kōlea return.

I read and enjoy all your kōlea stories. (Forty people, for instance, named their bird. My favorite name this year: Get chance.)

Thank you for your patience as we continue working on …

Kōlea gathering at a Ford Island field. ©Susan Scott

Kōlea gathering at a Ford Island field. ©Susan Scott

April 14, 2024

Yesterday a friend and I spent a pleasant hour on Ford Island sitting in lawn chairs while staring at 38 dots in a dry grassy field. Then we packed up, drove to Tripler Army Medical Center and spent another hour staring at a similar bunch of dots in another grassy field.

This might not sound exciting, but for us kōlea fans, we were whooping it up. It’s April. Time to watch the plovers party.

Roger Kobayashi unfolds chairs for our kōlea watch. ©Susan Scott

Roger Kobayashi unfolds chairs for our kōlea watch. ©Susan Scott

Okay, the birds aren’t exactly partying. A few pecked around in the ground, and I watched one female take flight and land near a male (photo below. ) But then the two, as well as the rest of the flock, just stood there.

From our distance, the male/female mix seemed about equal. ©Susan Scott

From our distance, the male/female mix seemed about equal. ©Susan Scott

I was there because on April 7th, birder and photographer, Roger Kobayashi, emailed that he saw dozens of kōlea in those two areas, and offered to take me there (military ID required for both places.) Because the birds don’t migrate until late April, and some in early May, we both thought this plover gathering was early.

But there they were, not exactly packed together but a lot closer than we see them all winter. We kept our distance so as not to disturb them.

The black dots in this Tripler Army Medical Center (pink building) field are kōlea. ©Susan Scott

The black dots in this Tripler Army Medical Center (pink building) field are kōlea. ©Susan Scott

As we watched, Roger and I wondered if there was enough food in those fields for that many birds (40 to 50.) Is bug abundance the reason they chose these particular areas? Do the birds return to their winter foraging grounds to keep their weight up? How does each bird know it’s fat enough to make the migration? Where do these flocks go at night? Why gather three weeks early? Are males and females pairing up? Does one bird decide the moment to migrate and the rest follow? Are kōlea gathering in other places now?

After Roger contacted me with the gathering news, I drove to Kualoa Park to see if kōlea are gathering there. They were not. I’ll keep checking. ©Susan Scott

After Roger contacted me with the gathering news, I drove to Kualoa Park to see if kōlea are gathering there. They were not. I’ll keep checking. ©Susan Scott

“It’s amazing how many things we don’t know about these birds,” Roger said.

True. But the mystery of migration is part of the fun. It’s thrilling to see our plovers change into their breeding colors and start moving around, because we know the epic undertaking these seven-ounce birds (up from winter …

A happy Joshua Fisher, USFWS Invasive Species Biologist, holds the elusive kōlea he finally caught with a netgun. Wally Johnson photo

A happy Joshua Fisher, USFWS Invasive Species Biologist, holds the elusive kōlea he finally caught with a netgun. Wally Johnson photo

December 13, 2023

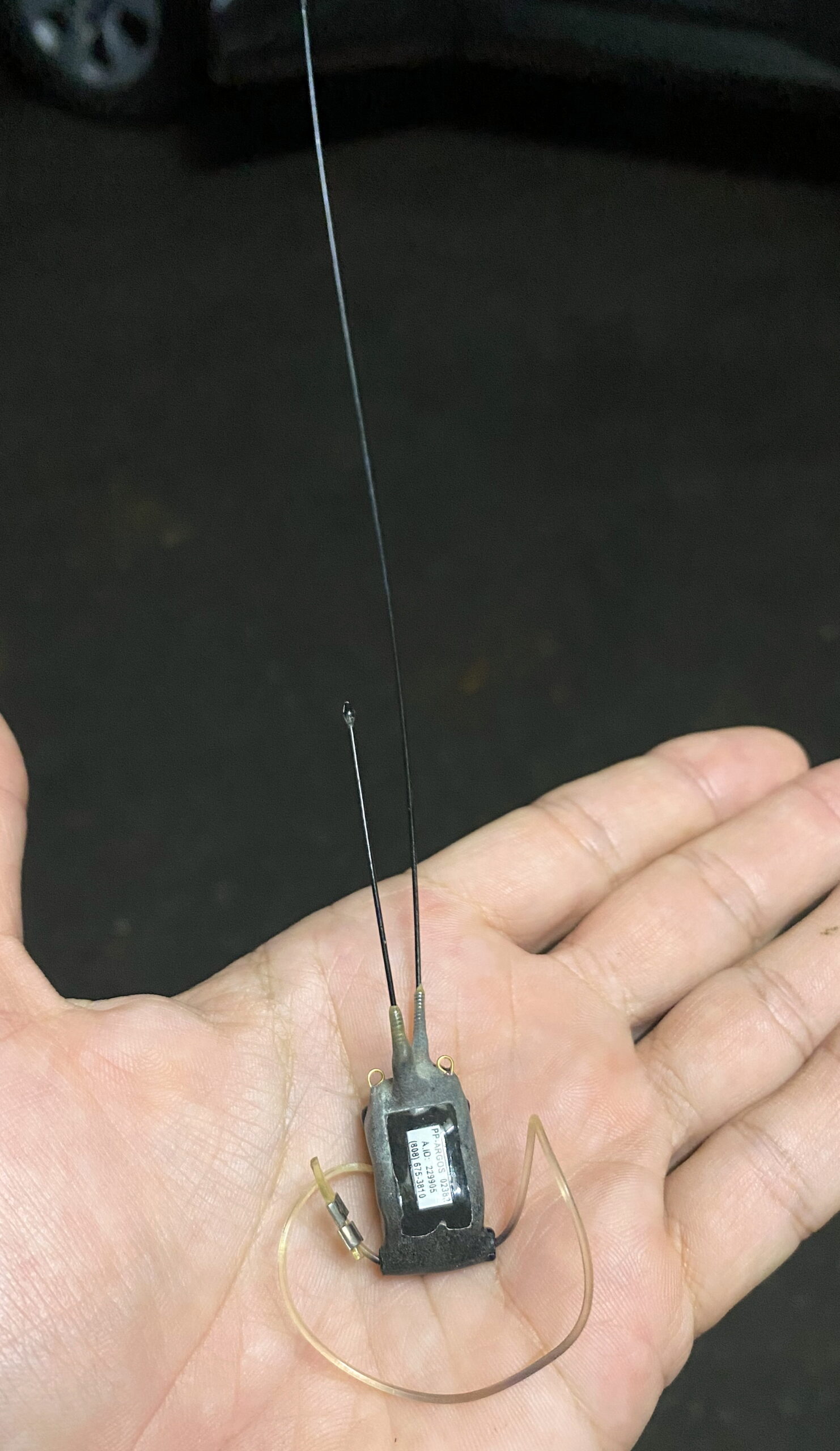

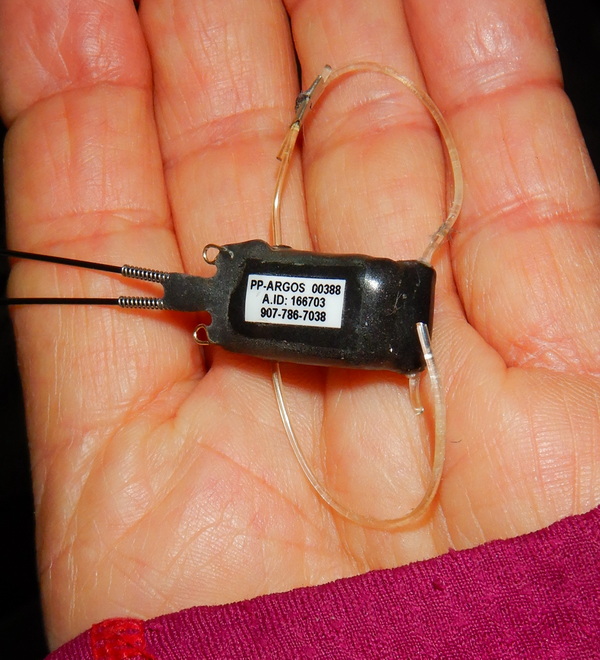

Two years after researcher Wally Johnson and countless volunteers fitted 20 Punchbowl kōlea with satellite tracking tags, four birds still carried their tiny backpacks. Time after time, Wally and helpers arrived in the cemetery with headlamps, cameras, mist nets, and netguns to recapture the birds. Besides relieving the kōlea of their no-longer-functioning tags, Wally wanted to see how they had fared physically. Each of the four have flown two round-trips to Alaska and back, or about 12,000 miles, carrying the tags.

Unfortunately, the batteries in these satellite-signaling devices only have enough charge for one season. Total weight of the device and harness is a bit less than one U.S. nickle. Wally Johnson photo

Unfortunately, the batteries in these satellite-signaling devices only have enough charge for one season. Total weight of the device and harness is a bit less than one U.S. nickle. Wally Johnson photo

But those kōlea were geniuses at staying just out of reach, dodging nets with such precision we joked that they could read our cars’ license plate numbers. Finally, persistence paid off. On November 29th, Joshua Fisher, a USFWS biologist and netgun expert, caught one of the four. And good news: After removing the tag and examining the bird, Wally saw no evidence that the device and its harness had caused the bird any harm.

Josh with his hard-earned prize kōlea, November 29, 2023. Wally Johnson photo

Josh with his hard-earned prize kōlea, November 29, 2023. Wally Johnson photo

Wally Johnson and partner Diane Smith untangle the kōlea from the net. Josh Fisher photo

Wally Johnson and partner Diane Smith untangle the kōlea from the net. Josh Fisher photo

Leg bands and tracking tags are the only way to learn about Pacific Golden-Plovers’ age and travels. Such “jewelry” seems a lot for a little bird to carry, but apparently it doesn’t phase the hardy kōlea. Wally found no feather, body, or leg damage to this bird after two round-trip migrations. Josh Fisher photo

Tom Fake and Mr. X win a photo finish

Wally and his team of volunteers recently celebrated another achievement in Punchbowl Cemetery. A kōlea named Mr. X, named after its chosen wintering site in section X, has exceeded the kōlea longevity record. Wally was thrilled to announce with confidence that Mr. X is at least 21 years, 5 months old.

Mr. X with his 21-year-old aluminum band. Tom Fake photo

Mr. X with his 21-year-old aluminum band. Tom Fake photo

The former plover to hold the longevity title was a Bellows Air Force Station bird, also banded by Wally, that lived for at least 21 years 3 months.

Before Mr. X could be officially declared the oldest plover on record, Wally needed proof. This was no easy task. The bird had lost his three colored plastic bands that Wally added with the metal band for ID purposes. Last year, plover counters noticed that only one red plastic band remained. This year, only the metal band remains.

In order to be sure that this is Mr. …

November 12, 2023

Thank you for joining the Hawaii Audubon Society’s annual statewide Kōlea Count. From December 1st through March 31st, we ask Hawaii’s participants of Big Counts to count kōlea in a park, cemetery, golf course, or other area claimed by kōlea as winter feeding sites. Little Counts are a way to note the arrival, departure, and behavior of a single bird that spends the winter in your backyard, street corner, or school grounds.

Once a plover survives its first year in Hawaiʻi, the bird returns to that precise place year after year. Foraging patches range in size from about one acre to a football field, depending on the abundance of crawly things in the patch. Kolea eat anything they can catch and swallow, including slugs (above), cockroaches, centipedes, and spiders. ©Pat Moriyasu

Once a plover survives its first year in Hawaiʻi, the bird returns to that precise place year after year. Foraging patches range in size from about one acre to a football field, depending on the abundance of crawly things in the patch. Kolea eat anything they can catch and swallow, including slugs (above), cockroaches, centipedes, and spiders. ©Pat Moriyasu

Choose a site from this list and email your choice to me, Susan Scott, here. If your area isn’t listed, tell me and I’ll add it. Please count, and report separately, your place at least three times throughout the season to account for birds that might have been startled into flight.

When a disturbance passes, a plover returns to its chosen patch, such as this bird at popular Ko Olina Lagoon 3, January 2023. ©Susan Scott

When a disturbance passes, a plover returns to its chosen patch, such as this bird at popular Ko Olina Lagoon 3, January 2023. ©Susan Scott

In recording our observations, we kōlea fans gather facts that help researchers learn more about the birds, and in that, help them thrive and survive. For instance, when people have noticed kōlea in late July and early August, a common question is: “Isn’t this early for the birds’ return?”

No. This summer and fall, observers reported more birds arriving in August than September. When I shared this fact to longtime plover fan and counter, Sigrid Southworth, she said, “And all these years, we said they arrived in September.”

A big mahalo to plover lovers for taking the time to report arrival dates, and to shorebird researcher Claire Atkins of UHM for compiling results in the below graphs. Also, thanks for sending pictures. If you have photos to share, please email me and I’ll send a link.

October 17, 2023

Aloha, kōlea fans. Our adult plovers have returned home (I consider Hawaiʻi their home since they spend nine months of the year here.) The birds are busy, busy, busy, eating to regain the fat stores they used up during their 3,000-mile nonstop flight to the Islands.

My bird, Jake, is exceptionally bold this year, stepping close to my lanai for his scrambled egg. He looks like a different bird from the last time I saw him, April 25th. He’s thin now and in winter attire. Like all plover lovers, I’ll enjoy watching the transformation.

Jake arrived August 11th this year. Here he is this morning eating scrambled egg, rich in fat and protein, and just what he needs. ©Susan Scott

Jake arrived August 11th this year. Here he is this morning eating scrambled egg, rich in fat and protein, and just what he needs. ©Susan Scott

Our Jake, April 25th, plump and dressed to the nines. ©Susan Scott

Our Jake, April 25th, plump and dressed to the nines. ©Susan Scott

Thank you to all who reported plovers’ 2023 arrival dates and places. In that, you help us learn more about our much-loved native birds. So far we have 390 entries with a total of 1,355 birds reported. Because this summer’s offspring can still arrive in November, arrival reporting continues through November.

Photographer and kōlea fan, Robert Weber, shared this photo he took of a kōlea flock near Kahuku on October 13. These birds may be summer offspring that made it from Alaska to Hawaiʻi. Plover youngsters, have no adult guidance. Navigation is by instinct.

Photographer and kōlea fan, Robert Weber, shared this photo he took of a kōlea flock near Kahuku on October 13. These birds may be summer offspring that made it from Alaska to Hawaiʻi. Plover youngsters, have no adult guidance. Navigation is by instinct.

On December 1st, the Kolea Count begins again. Please see the places I’ve listed here where you can count. If I didn’t include your site, let me know and I’ll add it. Email me your choice in the contact tab and I’ll mark it as taken. X marks the spot.

If you need some good news for a change (and who doesn’t?), join us at the Hawaii Audubon’s annual dinner meeting at Atherton Halau. I’ll be giving a brief slide show about our kōlea chick trips in Nome, an update on another favorite, Honolulu’s manu o Kū, and a few other happy bird doings.

Pat Hart, the man with the mellow voice who shares bird songs and bird facts on Hawaii Public Radio’s Manu Minute, is our guest speaker. Just hearing our birds sing and Pat’s pleasant voice gives me a lift.

TICKETS HERE or at https://hiaudubon.org/

July 6, 2023

Twenty Hawaiʻi Audubon Society members left Nome last week uttering a phrase few Alaska prospectors get to say: “We struck gold.”

Gold chicks, that is. During a trip that organizers named “Kōlea Quest 23,” four Pacific Golden Plover chicks thrilled us to our toes by hatching about two hours before we had to board the plane for home.

Chicks hatch in the order the female laid the eggs. The top center chick, still wet, was the last to hatch. The parents immediately pick up the empty eggshells and drop them far from the nest, since the white shell interiors are a visible clue to predators. The flesh-colored bumps are the chicks’ long, adult-size legs folded beneath them. ©Susan Scott

Chicks hatch in the order the female laid the eggs. The top center chick, still wet, was the last to hatch. The parents immediately pick up the empty eggshells and drop them far from the nest, since the white shell interiors are a visible clue to predators. The flesh-colored bumps are the chicks’ long, adult-size legs folded beneath them. ©Susan Scott

We knew the odds of finding kōlea chicks were low given that shorebird nests are incredibly hard to find on the vast Alaska tundra. Also, the hatching had to be within our five-day visit, and even if they hatched, we had to get to the chicks before they left the nest and started running round eating insects and berries. Kōlea parents warm and protect their newly hatched chicks, but do not feed them.

This photo from one of Wally’s past trips shows a male parent protecting his newly hatched offspring. © O.W. Johnson

This photo from one of Wally’s past trips shows a male parent protecting his newly hatched offspring. © O.W. Johnson

Our chick-viewing chances fell even further when Nome resident and guide, Carol Gales, of Roam Nome, sent pictures of area roads in early June. Snowfall this year, she emailed, was heavy and the thaw was late.

Late snowfall leaves little for newly arrived kōlea to eat. © Jim Dory

Late snowfall leaves little for newly arrived kōlea to eat. © Jim Dory

After their 3,000-mile nonstop flight, kōlea need nourishment fast. When mosquitoes and other insects hatch late due to cold weather, kōlea eat freeze-dried berries from the previous fall. © Jim Dory.

After their 3,000-mile nonstop flight, kōlea need nourishment fast. When mosquitoes and other insects hatch late due to cold weather, kōlea eat freeze-dried berries from the previous fall. © Jim Dory.

Optimism ruled, however, because we had plover expert, Wally Johnson, with us as well as his as his long-time assistants, Nancy and Paul Brusseau of Anchorage. We weren’t off the plane an hour when those researchers were off looking for plovers.

To find a nest in the vast tundra, Alaska researchers, Nancy and Paul Brusseau, watch where a flying kōlea landed. Craig Thomas (my husband) in shorts, works hard here supervising. ©Susan Scott

To find a nest in the vast tundra, Alaska researchers, Nancy and Paul Brusseau, watch where a flying kōlea landed. Craig Thomas (my husband) in shorts, works hard here supervising. ©Susan Scott

Over the next couple of days the team found three kōlea couples, but only two nests. Hawaiʻi’s people-friendly kōlea become extraordinarily wary in their tundra nesting grounds because they’re loaded with predators. Foxes, jaegers, ravens, and raptors are constantly on the prowl for tasty eggs and scurrying chicks.

One of the two discovered plover nests was near a road and easy to check, but as the days wore on, and the eggs hadn’t hatched, we resigned ourselves to not seeing chicks. Even so, the plover eggs were a …

Kōlea in flight, Kaena Point. ©Leslie MacPherson, DLNR.

Kōlea in flight, Kaena Point. ©Leslie MacPherson, DLNR.

April 27, 2023

Goodbye and good luck

Since late March, kōlea watchers have been reporting behavior changes in the birds they’re watching. Some say their birds became exceptionally active and friendly. (See my April 5th post about our bird, Jake.) Others noticed that their bird began to tolerate other birds in its territory. One plover fan reported that her plover started making soft cheeping sounds, as if trying to communicate.

Our male, Jake, (left) usually defends his foraging territory from other birds but come April, he tolerates company, such as this attractive female. ©Susan Scott

Our male, Jake, (left) usually defends his foraging territory from other birds but come April, he tolerates company, such as this attractive female. ©Susan Scott

The big question we plover followers had this month is: Where are the kōlea gathering for the big departure?

It’s a good question, one that Kolea Count is helping answer. Since early and mid April, plover watchers have reported that their bird is gone. It’s not likely they went to Alaska that early, because others reported flocks of 8-to-60 or so individuals gathering in fields at Ford Island near the NOAA building, Tripler Army Hospital, the lower campus of UH, and Diamond Head Crater.

Plover fan, Roger Kobayashi, escorted me onto Ford Island (military ID required) to see the gathering near the NOAA building. ©Susan Scott

Plover fan, Roger Kobayashi, escorted me onto Ford Island (military ID required) to see the gathering near the NOAA building. ©Susan Scott

By yesterday, April 26th, Roger reported that the birds were gone from Tripler. I also checked Kailua Beach Park and Kualoa Regional Park. None.

With no reports of the exact liftoff moment, it’s hard to say the precise day our plovers leave for Alaska. It’s probably safe to say that as of today, April 27th, most of Hawaiʻi’s kōlea are winging their way, nonstop, to their breeding grounds, 3,000 miles away. Wally Johnson, who is following reports, emailed: “Looks like departure is on schedule. Tough to get precise data, but appears to be about the same timing as last 40+ years!”

Come July and August, our kōlea will repeat this astonishing journey when they return to Hawaiʻi. We plover lovers will welcome them back with open arms.

Hawaiʻi Audubon board member and kōlea fan, Pat Moriyasu, shot this funny photo of a kōleaʻs “skirt” during one of our blustery days in early March.

Hawaiʻi Audubon board member and kōlea fan, Pat Moriyasu, shot this funny photo of a kōleaʻs “skirt” during one of our blustery days in early March.

Wally Johnson’s multiple migrations

In March, 2022, plover researcher Wally Johnson and volunteers from the Hawaii Audubon Society caught 30 kolea in mist nets at Punchbowl Cemetery for a successful migration study. To relieve the birds of their tiny backpacks, as well as to recharge the depleted batteries and reuse the $1,500-each devices, Wally returned in September to capture the birds carrying tracking devices (below photos.)

After repeated attempts, Wally and volunteer teams caught all but four tagged birds. Everyone involved was disappointed that we failed to recover four devices, but we tried hard.

During an August 10th Hilo visit, Hawaii Audubon board members Dr. Wendy Kuntz and Susan Scott, (me, in photo) admire this school’s welcome sign for its mascot, the Kōlea. ©Wendy Kuntz

During an August 10th Hilo visit, Hawaii Audubon board members Dr. Wendy Kuntz and Susan Scott, (me, in photo) admire this school’s welcome sign for its mascot, the Kōlea. ©Wendy Kuntz

December 12, 2022

Does a GPS signal interfere with a Kōlea’s migration? That was the question Wally Johnson set out to answer in March when he and a team of researchers and volunteers tagged 30 Kōlea at Punchbowl Cemetery (March 30 NEWS.) All 30 birds were fitted with colored leg bands for identification. In addition, 10 birds carried live GPS backpack devices, and 10 carried dummy backpacks. Ten had no backpacks at all.

This bird carried, round trip, a GPS tag labeled DUMMY. It was the same weight and size as the live tags, but did not transmit a signal. ©Susan Scott

This bird carried, round trip, a GPS tag labeled DUMMY. It was the same weight and size as the live tags, but did not transmit a signal. ©Susan Scott

By the end of April-early May, all 30 birds had migrated. Then came the waiting, and the nut of the investigation: Which of the study birds would return to Punchbowl?

Hawaii Audubon volunteers answered the call to find out. Armed with cameras and binoculars, Kōlea watchers took turns driving through Punchbowl almost daily from mid-July through September to look for, and record, the study-birds that had made the round trip.

The result gave Wally photographic evidence to the question of whether GPS signals sent to satellites from tiny transmitters the birds carried on their backs interfered with their migration: The answer is no.

This male, nicknamed Mr. Necker, flew to Alaska, then Russia, then to Necker Island in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument where his signal stopped. The team was surprised and delighted to recapture him in Punchbowl Cemetery on October 10th in the exact spot he was tagged in March. We know the bird’s sex from his springtime feather colors, not his above October colors. ©Susan Scott

This male, nicknamed Mr. Necker, flew to Alaska, then Russia, then to Necker Island in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument where his signal stopped. The team was surprised and delighted to recapture him in Punchbowl Cemetery on October 10th in the exact spot he was tagged in March. We know the bird’s sex from his springtime feather colors, not his above October colors. ©Susan Scott

The birds with transmitting backpacks, dummy backpacks, and no backpacks returned this fall at about the same rate: 80 percent. Wally Johnson reported this finding—that GPS locating signals have no apparent negative effects—in the 2022 summary of the Alaska Shorebird Group.

A large part, and purpose, of Kōlea research is teaching. Here’s Wally shows volunteers and students a recaptured plover’s flight feathers. ©Susan Scott

A large part, and purpose, of Kōlea research is teaching. Here’s Wally shows volunteers and students a recaptured plover’s flight feathers. ©Susan Scott

Wally shows volunteers and students the wear on a kōlea’s flight feathers. The bird will drop these hard-used feathers and grow new ones, but gradually, so as to not lose its ability to fly. ©Susan Scott

Wally shows volunteers and students the wear on a kōlea’s flight feathers. The bird will drop these hard-used feathers and grow new ones, but gradually, so as to not lose its ability to fly. ©Susan Scott

B